Andrew Calimach

In the Jungle, the Gentlemen; in Town, the Savages

Reproduced here by permission of the author.

Verba volant, scripta manent—The spoken takes flight, the written remains. It was thus that the Romans phrased the warning that the written word is lasting proof of matters that at some future moment may prove inconvenient, or embarrassing. From that perspective, perhaps societies that employed the written word are at a disadvantage compared to those that did not make use of it. That certainly is the case with the Greeks today, who have to contend with the fact that the sacred texts of their ancestors, what we think of today as Greek mythology, enshrine the love between one male and another. That is not a problem faced by societies that never left a written record, like the African cultures of the Azande or the Buganda, for example. But even though the Greek states and the African nations did not share a common culture, they most certainly shared a common humanity. How did that play out on the stage of history, in the domain of male love?

The myths the ancient Greeks left behind illuminate the present with surprising insights, at times uncomfortably modern. Choose - the myths seem to invite - choose to live as brave and just men, or to be banal and rapacious. This tension between the gentleman and the savage is one the Greeks played out on the field of battle between nation and nation, in the passionate encounter between a man and a woman, and even more so in the one between a man and a youth. That is a battle too, the myths seem to say, a battle not with the other but with oneself, whether in a walled Greek city, or on the streets and in the schools of today.

How then did Greek men rise to that challenge, to live as gentlemen in an erotic universe simultaneously exalted and degraded, and what does it have to do with the modern world? In the realm of love, their myths tell us the Greeks were not satisfied with half a portion, but insisted on savouring the feast of love entire, the male and the female. Nor did they make the mistake of seeing the two as equal, or equivalent in any way. The drama played out with a woman was very different to the one played out with a youth. After all, there was an essential difference between the two. Women were for marriage, an arrangement usually worked out between the suitor and the father of the girl. It was primarily a utilitarian matter, and only incidentally an enjoyable one. Wives produced handicrafts, produced pedigreed children, and cemented political unions. They were given little, and much was taken from them, not least their freedom.

With youths, ideally, it was the opposite. The man was the one to give his love, his skills, his power, and his wealth. It was, as it still can be today, an exercise in altruism, and in the transmission of manhood. “It is not among women and children that a man’s spirit is forged,” the Greeks seem to have believed. With boys an elaborate game of courtship was played, one often mediated by gifts. It is common knowledge that Greek men offered boys fighting cocks, horses, pets, playthings, battle gear, and delicacies. Were the youths being bought off? Or were they being taught a lesson in generosity? In Socrates’ Athens, the youths too were expected to present gifts to their lovers. Eager for honorable love and friendship with a good man, even as youths still are today if given half a chance, they traditionally gave their lovers a certain type of cake, purposely made to be offered by an eromenos, as young beloveds were called, to his erastes, or adult lover, in order to excite his interest. Socrates himself was said to have once brought home just such a cake, driving his wife, Xanthippe, into a fit of jealous rage, certain it had come from his eromenos, Alcibiades. She grabbed the offending pastry, dumped it out of its basket, and trampled it underfoot. Her husband just burst out laughing, telling her, “Now you won’t get any of it either.” In one way, however, the distinction between relationships with women and with boys was not quite absolute. It is a friend and student of Socrates, Xenophon, who points out in what way they were similar. Just as marriage with a woman could be contracted only with the approval and permission of her father, an ethical love relationship with a boy could only unfold under the oversight of that boy’s father. “Nothing,” Xenophon tells us, “[of what concerns the boy] is kept hidden from the father, by a truly noble lover.”

Athenian warrior and his eromenos

In the exchange between a man and a youth, what was actually given and received was the freedom to be fully male. For the boy it was the freedom to enter into the world of men, for the man the freedom to pass on his wisdom and skills to a worthy successor, and for both the freedom to delight in that most masculine of affections, the love between one male and another. For the Greeks, however, freedom was meaningless in the absence of restraint and moderation. In order for men to be free to love youths, a strict form evolved that channelled that freedom along certain paths, and barred others. There were many limitations and restrictions, but the most important was what not to do in bed, a despised act that came under the rubric of hubris, a word used in a very different sense from the one current today, a sense diametrically opposite to the freedom that legitimate lovers attained. One way to render it would be “sexual subjugation.” Above all, it was the anal penetration of one male by another (though oral penetration was also deemed degrading) that the Greeks despised and saw as an act not of love, but of oppression.

For teaching morality, few means are as effective as tales. The myth of Laius, father of Oedipus, is a story that the Greeks devised to warn young men against falling into the trap of blind lust. Laius, the tragic king of Thebes, was for the Greeks a paragon of many forms of hubris. It was due to an act of a more ordinary sort of hubris that he died, an ancient example of what we might now call road rage. His murder, at the hands of a wayfarer who did not recognize him as his own father, a wayfarer whom his men had shoved off the road in order to make way for the king, does not occur in a vacuum. It is divine retribution for a far more outrageous act of hubris, one that Laius had committed in his youth. After fleeing his home town for his life and being granted safe harbour in the house of king Pelops, he pays back his host by kidnapping and raping that man’s son. Here hubris no longer means excessive pride or arrogance, but sexual outrage. How did the Greeks conceptualize this sexual violation of a boy by a man, a violation they understood to be intrinsic to the act itself, in no way less foul if the victim submitted willingly?

Plato describes it in his Laws, where he indicts not sex play between males, as practiced for example in the cultural institution of Greek paederasty, where erotic play short of penetration was allowed (contrary to what many readers of Plato have systematically misunderstood throughout the years, taking Plato’s words to be a blanket condemnation of “homosexuality”), but strictly the infliction of hubris upon a boy or a man. Far from criticizing the erotic—but moderate and dignified—mainstream love of men for boys that the Greeks labeled eros dikaios, or legitimate love, a custom he practiced himself, Plato exclusively condemns the buggery of males, mature or young, willing or not: “If we were to follow in nature's steps and enact that law which held good before the days of Laius, declaring that it is right to refrain from indulging in the same kind of sexual intercourse with men and boys as with women, and presenting as evidence thereof the nature of wild beasts, and pointing out how male does not touch male for this purpose, since it is unnatural ...

That is the rule that Laius breaks. Thus he was known throughout Greece not as the first mortal man to make love to boys, an act the Greeks traditionally practiced honorably, face to face between clenched thighs, but the first to turn the boy around in search of an invasive consummation, one which in the end consumes him as well as his victim. Here is the myth, a recounting based on the ancient fragments, with a bit of modern plaster to re-bind the sundered sections . . .

LAIUS AND GOLDENHORSE

A weary band of travellers straggled to the gates of king Pelops’ palace in Pisa and hailed the guard: “Open up! Laius, prince of Thebes stands before you,” their chief called out. The gates swung open and the men stumbled in, a few battle-hardened warriors and one gangling youth. When they had rested, their chief spun his tale: Usurpers had grabbed the reins of power in Thebes, killed the king and all who stood in their way. They were out to murder the boy Laius too, for he was next in line to the throne. Instead, in the dark of night, a few loyal subjects had fled with the prince. Now he needed a protector.

Pelops welcomed Laius, and made room for him at table next to his sons. The twins, Atreus and Thyestes, he had fathered with his faithful wife, Hippodamia. Handsome little Goldenhorse, however, he begot on the sly with a nymph. Pelops kept him close, even though Hippodamia could not stand the sight of the curly blond imp. Laius ripened into manhood in Pelops’ house, but he hankered for the throne of Thebes, rightfully his, and was sick of living like a beggar in another man’s domain. The twins blossomed into men like gods, and Hippodamia swelled with pride to behold their strength. She spared no effort in grooming them for power, determined that someday Pelops’ kingdom would be theirs.

That was the last thing Pelops wanted. He loved Goldenhorse the best of all his sons, and meant to set him on the throne. To carry out his plans, however, he needed a man he could trust completely. He summoned Laius, and let him in on his designs: his son had to be taught the skills of princes, for he had much to learn before he could rule. Pelops charged Laius to tutor Goldenhorse, to teach him the charioteer’s art. Laius felt obligated to repay the king’s welcome. He bowed low, thanked Pelops for the honor, and pledged to fulfill his wishes to the letter.

From that day on, each rosy-fingered dawn found Laius and the boy hard at work, riding the polished bentwood chariot, putting the rapid horses through their paces. Goldenhorse was glad to set childish games aside, to learn the manly skills. The time of the Nemean games was drawing near, and his heart pounded with thoughts of glory, racing other Greek princes, even winning a champion’s laurels, if so the gods chose. But as Laius coolly taught Goldenhorse to turn the spirited horses to his will, his heart flamed with desire for the boy. Time and time again he tried to win his love, with no success.

The games were about to start, so Laius and his pupil set out, with Pelops’ blessings, for the green valleys of Nemea. Claiming to spare the boy’s strength for the races, Laius took the reins. But when they reached the famous city he did not halt, but picked up the pace instead. Goldenhorse pleaded, begged, and threatened, but Laius just flogged the team on, breakneck on. He stopped his ears to the boy’s cries and did not curb the horses’ headlong career until the towers of Thebes loomed overhead. There Laius claimed the throne as his birthright . . . and Goldenhorse as his beloved. Laius turned the youth face down upon his bed and lay with him as with a woman. “I know what I am doing, but nature forces me,” he told the furious prince. The Thebans, overjoyed at the return of their rightful king, turned a blind eye to the outrage committed behind the closed doors of the royal palace.

The moment Pelops learned Laius had kidnapped his son, he called his men to arms and marched on Thebes. Nor did Hippodamia dawdle, she was not going to miss this chance to rid herself of that bastard stripling for good. She secretly summoned Atreus and Thyestes. They leaped aboard a chariot and raced away, hell-bent for Laius’ palace. Goldenhorse was overcome with joy to see his beloved brothers, grateful to be freed from Laius’ clutches. But as soon as the three brothers walked out the palace gates, the twins grabbed hold of the boy and pitched him head-first into a well, drowning him in its dark waters.

Before long, Pelops’ army was arrayed many deep before the walls of Thebes. The king’s emissary galloped into the city, only to discover that Goldenhorse was dead. Pelops shook with rage and grief. “Never again shall those two sons of mine set foot upon the soil of my country,” he thundered. And he wanted nothing more to do with his wife. Hippodamia fled into exile, and then hung herself.

When king Pelops dealt with Laius, however, he remembered the love god’s power to turn the heads of men, and spared his life. But the king laid a father’s curse upon Laius – childless to remain, or meet death at the hand of his own son – and called down the wrath of the gods upon all Thebes. The Sphinx winged down upon the town, snatching and devouring Theban boys, while horrors without end befell Laius and his kin: his son murdered him, then fouled his own mother’s bed, sowing his seed where he had been sown himself – doomed Oedipus.

* *

*

The closing image of the Sphinx swooping down from the sky, snatching up the boys of Thebes only to consume them, evokes the opening passage of a more familiar myth, that of the abduction of young Ganymede by lovelorn Zeus in the form of an eagle. The symmetry is hardly accidental. The two myths were designed to be polar opposites of each other, like a black and white photograph and its negative. Where the Laius myth teaches the perils of self-indulgence and of surrendering to bestial impulses, the Ganymede myth charts a course for the generous and self-controlled. In contrast with the criminal kidnapping of Pelops’ son, we now witness a ritual abduction patterned on an ancient Cretan aristocratic initiatory custom. Instead of being betrayed and robbed, like the father of Goldenhorse, the father of Ganymede is enriched, and rejoices. Where Laius deprives Goldenhorse of everything of value, and dishonors him, Zeus offers Ganymede the best gifts a mortal could aspire to, and the highest honor - that of joining the gods in Heaven. What more eloquent foil could the Greeks have devised than to juxtapose the death of a desecrated Goldenhorse to the eternal life and eternal youth of a transfigured Ganymede? Finally, unlike the distraught Goldenhorse, shown by Greek painters struggling to flee his abductor, Ganymede is often depicted with a beatific smile on his face. It is a telling attribute, even more so than his beauty.

Much too much is made of the alleged Greek interest in boys alone, and the alleged ridicule they directed at men who loved other men. Who, pray tell are the famous heroic couples? Achilles and Patroclus? Orestes and Pylades? Alexander the Great and Hephaestion? The Greeks wreathed in dignity and beauty the love between one adult warrior and another. Why would they not? How could they have truly manifested an authentic masculinity had they cast out such an important part of male experience for many, if not for all? In no way does it render their achievement less significant that they judged that manhood was fatally compromised by unbridled behaviour, in particular by that act in which one male uses another as a woman. On the contrary. Aping the heterosexual act with each other sullied both lovers and turned them into a laughing stock, yet tremendous latitude for legitimate passion remained, echoed by Achilles' lament at the reckless death of Patroclus in battle, when he blames his beloved for having “no reverence for the sacred bond of the thighs, ungrateful for all those kisses . . .”

It is a feature of our shared humanity that we bring culture to all aspects of life, raising it from its original brutish, animalic level, to refined and sophisticated forms. That can be seen in the ways we dress, in the ways we cook and eat our foods, in the ways we build elegant homes for ourselves as means allow, and in countless other ways, including, sadly, in the ways we fight our wars. In just this fashion the Greeks built their culture of elegant and honorable male love two and a half millennia ago. Though that elaborate culture was destroyed together with the rest of Greek civilization, we know about it from the written record they left, the myths, the philosophical tracts, the legal discourses. How about those nations that did not leave such histories for peoples of the future to ponder? If such peoples had established and then at some later date abolished such male love traditions, we can assume that knowledge is lost forever. It is for that reason that so many people in Africa today assert that the love between one male and another is surely a foreign import. That contention, however, can be proven false. Though we do not have a body of literature documenting the thoughts and actions of pre-modern African peoples written in their own hand and language, in a couple of fortunate instances, a record of the male love practices of such African societies has been preserved. affording us a glimpse into a normalcy that no longer exists, its total absence being the only thing that permits us to imagine ourselves as “normal.”

In the second quarter of the twentieth century, among the Azande people, who are now scattered across the Democratic Republic of Congo, the South Sudan, and the Central African Republic, the anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard encountered the last vestiges of an ancient tradition of men’s love—mixed with mentorship, honor, and duty—between adult warriors and either young men, or adolescent boys. It is a kuru pai, an old tradition, in which Azande warriors and princes, usually members of the bachelor aparanga battalions, took in marriage, after paying a certain bride price, younger males as wives. As with the Greeks we see two different types of relationships integrated in one tradition.

The first is with young men at the peak of their physical ability, between seventeen and twenty years of age, whose bodies are fully grown and who can do a man’s work in every sense of the word. One can imagine that these youths commanded a higher bride price, reflecting their greater economic value. The mentorship aspect is still essential, since Azande men married late, in their twenties or thirties, and thus there was a clear difference of maturity and experience between the warriors and their assistants, but it is a mentorship much less demanding than the one required by a boy, as all who have raised adolescents know very well. In this first type of relationship we see love and friendship and collaboration between men of different ages. It should remind us of famous Greek relationships such as that between Achilles and Patroclus.

The second type is not a relationship between two men but between a man and a young adolescent boy, between twelve and sixteen. Perhaps men who could not afford a high bride price had to settle for a younger beloved. Or it may have been the free choice of those men with a soft spot in their hearts for the beauty and malleability of a boy, and who had the talent and the desire to take on the education of a young adolescent. We know that Azande men felt and expressed affection toward boys from the way aristocrats related to commoners. It seems that princes treated the boys in their entourage with great indulgence and tolerance, in contrast with their comportment with the adults, with whom the princes were severe and harsh.

As with the Greeks, all beloved youths, the younger ones as well as the older, played the roles of apprentices, partners, and lovers, until they became warriors themselves, and took on male companions in turn. As with the Greeks, the father of the youth was involved in the relationship—the lover, who was known as the badiya ngbanga, or “court lover,” offered the father a spear when he asked for the hand of the youth, or kumba gude, in marriage, and paid with more spears when the marriage ceremony took place, five for a good youth, and even ten for an exceptional one. There also seems to have been a system rewarding those men who fulfilled their obligations toward the family of the youth: when time came for the youth to join the ranks of the warriors, the father would frequently offer the man one of his daughters in marriage. The saying went, “If good for a boy, how much better for a girl!”

Men guarded their beloveds jealously, and if they caught another man courting their youth they would take that man before the king and demand payment in spears, as punishment for the offense. When warfare broke out, they would not allow the young boys to join them in battle, but had them wait behind in camp, and would relate to them stories of the fighting upon their return.

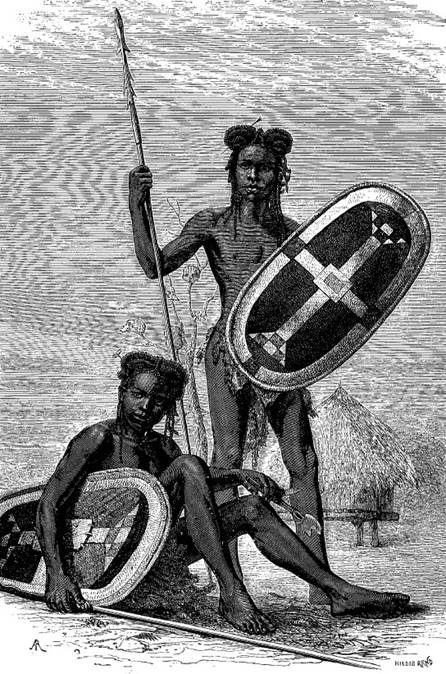

Azande warrior youths

The partners addressed each other affectionately, the lover calling his beloved diare, “my wife,” and the beloved addressing his lover as kumbami, “my husband.” During the day the wife’s duties included carrying the shield of his badiya ngbanga, helping cultivate the fields of his husband’s father, gathering firewood and bringing water, and cooking manioc and sweet potatoes for him and his lover to eat. At night, the youth kindled a fire beside his husband’s bed. The two then slept together, and their lovemaking was face to face, between the thighs, identical to that of the educated ancient Greeks. Evans-Pritchard reported that the Azande men who recounted their traditions to him expressed disgust at his mention of anal penetration.

A loving bond between a youth and his mentor, a dignified erotic union, lover teaching beloved, the embrace of their families, and service to the community, all these aspects combine to reveal a homegrown African version of Greek love at its best, proving that the fighting men of the Azande nation, living unlettered in the very heart of the African continent, were true gentlemen in the domain of male love, every bit as much as the fighting men of the Greek states at the peak of their intellectual and artistic glory. If only the male love legends of the Azande had survived, as have those of the Greeks, we might well encounter an ethos very similar to the one the ancient Greeks enshrined in the ur-legend of Zeus and Ganymede. That window is now closed, and only the Azande bards could open it, should any still be left, and should they still remember how.

If the Azande were the gentlemen of male love on the African continent, did Africans harbor savages in the style of Laius among them also? In stark contrast with the ethical love of the Azande warriors stands another tragic king, this time not a mythical one. He is the young ruler of the Buganda, the kabaka Mwanga II, torn between the traditions of his nations and those of the British colonizers. At that moment in history, when the influx of foreign men with their new foreign ideas was sapping the traditional authority and power of the Buganda king, even a man many times older than the teenage Mwanga would have been hard pressed to find a way to uphold the customs of the kingdom. But Mwanga was little more than a boy himself, prey to thinking in the absolute terms characteristic of his age. He reacted with aggression to what he perceived as disloyalty, and had forty five youths and boys, all of them pages who had been sent by their fathers to serve him, burned to death or beheaded to punish their treason. Aside from not recognizing the divine authority of the king and giving their allegiance to European missionaries, they had refused any longer to let themselves be sodomized by the young Mwanga.

It bears asking, were the Greeks, the Buganda, and the Azande all “homosexuals”? After all, the males of these nations habitually made love to other males, in one way or another, as a matter of course, and did not give that matter any special significance. Here is where we can see an even greater difference between those men, and the men of today. When we look at these pre-modern peoples we see a feature of masculine experience that was universal in many, if not most ancient lands. We see that men routinely loved youths as easily and casually as they loved women. Among these men of the past, if a distinction was made, it was not based on whom you loved, but how you loved. Thus we must take issue with those who take refuge behind the smokescreen of ahistoricity to claim that in Africa there was no homosexuality before the advent of the Europeans. That position is psychologically and historically implausible. All African cultures must have featured some form of love between males. The meld of friendship, drive for physical satisfaction, and love of male beauty, in whatever proportions, is common to all peoples. It likewise drives all to action, unless thwarted by some inculcated fear. Examples abound. Boys in the Congo played gembankango. They would chase each other through the forest, swinging from vines, in a game we might call “bugger the loser.” The Ashanti in Ghana had male slave wives, bedecked with “pearl necklaces with gold pendants” that followed their husbands in death, much as in the Indian suttee practice. Among the Wolof in Senegal cross-dressing men known as gordigen, “man-woman” were common. Along the Upper Volta river, handsome boys between the ages of seven and fifteen known as sorone were lovers of village chiefs, and were forbidden relations with women.

The most likely scenario is that male love in Africa was everywhere, manifesting in countless forms, indescifrable in most instances to foreign observers, or if perceived, left unmentioned out of embarrassment. Thus the burden of proof must rest upon those who would claim it did not exist. The only question that remains is whether the male love relations of any given culture followed a refined and considerate pattern, such as that exemplified by the educated Greeks and the Azande, or a more savage modality, like that exemplified by the myth of Laius, and the Buganda kabaka.

This crucial distinction might throw an illuminating light also upon the reflexive revulsion that male homosexuality still evokes in many people today, whether they admit it or not. Could it be the product of a culture clash between the sensibilities of an evolved society, and an unexamined association with one particular atavistic behavior irremediably at odds with those sensibilities? To take the Azande as an example, we can say that their tradition of male love was a complex custom, one that developed its form and structure over many centuries, if not millennia. It was a tradition socially constructive in many ways. It strengthened the community by making fighting men more effective. It established lasting friendships between young men, the basis of lifelong alliances. It was a means for experienced warriors to transmit important skills to younger men. If their beloveds were still adolescent, it helped them cross from adolescence into adulthood. It strengthened the social texture of the community, forming bonds of friendship and mutual assistance between families. And it accomplished these goals by elegant and dignified means, in that it did not subject the beloved to unclean practices that would have caused him pain and indignity in exchange for the pleasure taken by his lover, and that would have put him at risk of physical harm, incontinence, and disease.

An eternity of time and of trial and error had taught the Azande how best to configure the natural love between two males in order to maximize its benefits and minimize its dangers. Its social and psychological sophistication presumably was on a par with other features of Azande culture, as is suggested by its integration into the social structure of the community. This aspect radically distinguishes it from the new-fangled homosexuality of today, one that, from a historical perspective, was born yesterday. To achieve an equivalent level of integration, this long-repressed aspect of human experience must first recapitulate the millennia of evolution that informs modern man’s other pursuits, since right now it has more in common with the homosexuality of the American buffalo or of the orangutan, animals that, as zoologists inform us, also penetrate each other’s anuses when possessed by lust for another male, than with the traditions of more evolved same-sex love cultures, that take advantage of the constructive potential of love, while keeping in check the destructive power of sexuality.

The findings of zoologists impel us to revisit one of the more important arguments against anal sex advanced by ancient and more modern thinkers alike. Plato, Lucian of Samosata, and many other polemicists over the centuries have buttressed the argument that buggery is unnatural by holding up the paragon of an animal kingdom free of such sexual activity between one male animal and another. Modern science, however, not only refutes them but stands their argument on its head. Recent work has shown that the higher species indulge in same-sex relations with abandon, and that among some of these buggery is common. The moralists had it wrong. The argument that they ought to have made is not that men should abstain from copulating anally with each other because animals do not do it and therefore it is unnatural, but that they should abstain from it because only an unreasoning animal would do such a thing, normal perhaps for a beast or a savage, but unnatural for a thoughtful human being.

That is not to say that we humans are not subject to the forces of nature. In particular, natural selection could well play a role in what may seem on the surface to be a set of cultural attitudes based on subjective judgements. When an apparently subjective position is as widespread, across cultures and across time, and has such force as the reflexive abhorrence to anal penetration, we have to ask ourselves whether there are objective underpinnings to the apparent subjectivity. Could it be that the avoidance of anal sex has adaptive value? Certainly recent experience would point in that direction, as the gay culture’s fixation on the male anus has been nothing less than the opening of a Pandora's box, out of which continue to spill deadly diseases, social conflict, and a polarization of sexual desire that has impoverished the social space and the love life of most males.

The homosexual relations of our day are bereft of the centuries-old cultural roots that informed and enriched past traditions. Instead, the forms they take are subject to the latest fad, and to the influence of the media that consistently propagate the dangerous deception that anal sex is the essential and defining expression of love between men. That of course becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, especially when the media never mention the fact that the practice was a very minoritarian one before the sexual revolution of the sixties. As a result, erotic play between males has become inextricably identified in the public mind—even though it does not have to be and often is not of this sort—with anal penetration, a thing distasteful to any person not brainwashed by the sustained barrage of modern pro-sodomy propaganda.

That state of affairs is only partly the fault of those men who do engage in such relations with each other. The real blame must fall on those institutions, religious or colonial, that suppressed and destroyed the rich and highly evolved ancient traditions of socially functional male love. In their wake they have left a scorched and barren erotic landscape, in which a sterile orgasm-at-any-price homosexuality has sprung up. Unlike the constructive traditional homosexualities of the past, this homosexuality is unmindful of consequences and is not integrated into any social structures, unless we are to count its attempt to usurp the function of child rearing, an attempt that by pushing a false equality tramples on the right of every child to be raised by a father AND a mother. Are we to believe that the plight of fatherless children, a suffering recognized since antiquity, is now to be resolved by adding a second mother to the mix, or viceversa?! Would it not be far better for a gay man to join up with a lesbian woman, as many already do, putting the interests of the child before those of romance, if bringing up children was what they truly wanted? And are we to admire those male couples who wield large sums of money as a crowbar to separate mothers from their babies, hiding a dehumanizing act behind the mask of love and equal rights?

The only reason gay relations that involve copulation are at all sustainable is because they rely on the heroic efforts of modern medicine to rescue those who engage in such behavior from the diseases that so frequently plague them. All too often even these efforts fail, as we can see from the AIDS epidemic, one that has already taken the lives of millions, or looming epidemics, like the epidemic of anal cancer and the epidemic of untreatable, antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea. And who would be so foolish as to imagine that these epidemics will be the last? In reality, it is anal sex itself that should be seen as an epidemic, one that has spread to the detriment not only of the men who engage in this practice but of all of society, that now has to cope with the threat of infections spreading beyond the boundaries of the gay community, and with the tremendous financial burden of containing the plagues. Indeed, recent medical discoveries indicate that the use of Truvada, a daily pill, will prevent infection with the HIV virus, if taken by healthy people previous to any exposure. Its cost is $12,000 a year per person, money in effect spent by society so that men can bugger each other with relative impunity. Who is more mindless, the bugger, or the one paying for the act?

In all fairness, we must, however, recognize that we are all the victims of a double blindness. Most males who love other males, while styling themselves nonconformists, have marched lock-step to the beat of a destructive fashion that essentializes sodomy, a capricious and arbitrary choice that flouts an ageless human taboo found to a greater or lesser degree in every human society. As a result, those men who shape their love for other males according to this pattern of modern gay culture have done themselves great and lasting harm, they have sown strife in society, and they have earned the contempt of a large proportion of their fellow citizens. But the same citizens who condemn those homosexuals who brazenly bandy the banner of buggery while shutting their ears to all criticism by belittling their critics as “bigoted” and “homophobic,” the many citizens who express their repugnance at having anal sex increasingly touted in popular culture as normal behavior, and taught to children in the public schools as a legitimate sexual choice, they too have made a fatal error.

Those who tar all homosexuals with the same brush have taken leave of their senses as much as some of the men whom they accuse. In blaming all males who love each other for deviant behavior, the accusers have lost all discrimination, and condemn love in the same breath that they condemn immorality. The two however are totally separate matters. No man has the right to command another whom to love. To forbid another to love whom he loves is savagery of the highest order. Love is a force of nature whom no one can command. The torrent of love can not be dammed, it can only be channelled. Thus the only defensible argument of those who now condemn all homosexuals as savages, akin to cannibals or practitioners of human sacrifice, is for them to say to males who love other males, “Love whom you love, but express your love in a way that is compassionate, a way that promises lasting benefit instead of threatening insidious harm, a way that all reasonable men can admire.” At that point we may all discover what the Greek and the Azande gentlemen of old understood and put to good use: that the seed of male love can sprout in the heart of every single man, not just a select few, as long as that love follows a path that is beautiful and wise.

Postscript

In some languages the word "pederast" is a term, often used in contempt, to indicate a man who engages in anal copulation with another male, whether of a similar age or not. That is a very long way from its original, honorable meaning, more than two thousand years ago. How could such a radical shift have come about?

Most probably, it is a slap in the face of every man who has intended or pretended to love another, only to debase and harm that man or youth (as well as himself), be it consciously or unconsciously. Unfortunately, while the condemnation may be appropriate, the term is poorly chosen. A better term would be "anti-pederast," since the original pederasts were the very men, themselves lovers of males, who expressly rejected such activities in their relationships with their beloveds. It was they who, in order to communicate their morality and dissuade others from ever practicing buggery, conceived the archetype of Laius, "the first bugger," a man who not only paid for his crime with his life, but also with the destruction of his offspring to the third generation.

Occupying and stigmatizing the semantic territory of men who engage in ethical and constructive love relationships with other males has the inevitable result of fomenting a climate of ignorance regarding the possibilities of such relationships. Since this does not eliminate the feelings of attraction, desire, and love between males, the ultimate result is that many of these couples will end up doing precisely that thing which is wiser to avoid, engaging in buggery, knowing nothing about the existence and history of a more constructive and refined model for such relationships.